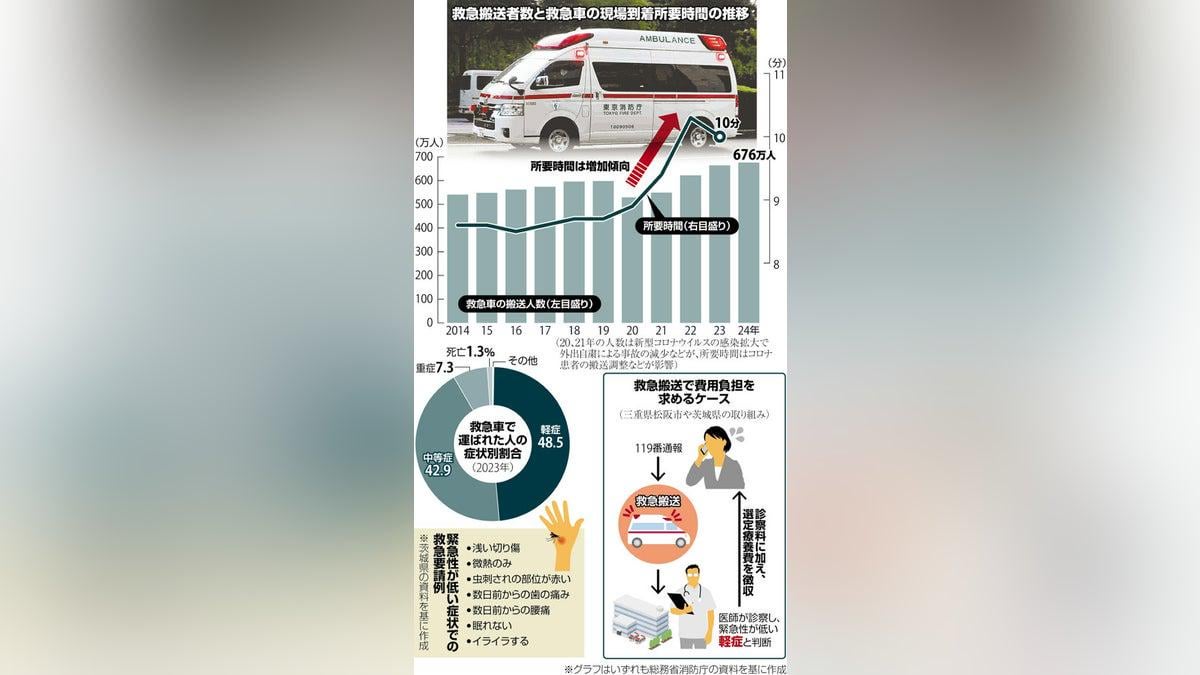

The number of people being transported by ambulance has increased, with a record 6.76 million people transported nationwide last year. However, about half of these cases involved minor injuries, and many emergency calls were not urgent. Some hospitals are starting to charge fees to patients with minor conditions, effectively making ambulance transport a paid service. This raises a question: should such charges be recognized?

Proponent Viewpoint:

In Mie Prefecture, a program started in June 2024 that charges a fee of 7,700 yen to people transported by ambulance who do not need hospitalization. This is similar to the “selected medical care fee,” which applies when a person visits a hospital with more than 200 beds without a referral. The increase in emergency transports, with 15,525 cases in Mie in 2023, prompted this move. Nearly 60% of these cases were minor injuries, creating delays for truly urgent cases.

The initiative aims to encourage people to reconsider whether an ambulance is necessary. Since its introduction, ambulance requests have decreased by 12.1% to 13,642 in 2024.

In Ibaraki Prefecture, 22 hospitals began charging non-urgent patients as of December last year. Within three months, the proportion of minor cases dropped by 5.3 points compared to the previous year.

The Japanese Society for Clinical Emergency Medicine discussed the de facto commercialization of emergency services, with 80% support in an assembly. Some believe that while fire departments don’t profit, such fees highlight the high costs of ambulance services, prompting their appropriate use.

Opponent Viewpoint:

There are concerns that charging for ambulance use may deter people from calling for necessary help. Some argue there are alternatives to charging fees, such as extending employment for paramedics and increasing emergency units.

Individuals with chronic conditions, like a 40-year-old student from Aichi Prefecture, feel anxious about fees; already relying on ambulance services, they fear costs might make seeking help harder.

Some experts, like Professor Asako Matsushima from Nagoya City University, argue that fees aren’t a solution. Charging might even increase misuse by people willing to pay if seen as a taxi service. She suggests a system that recommends alternatives for low-urgency cases instead of automatically dispatching ambulances.

Education on when it’s appropriate to call an ambulance is vital, as suggested by Kyoko Ama, a fellow at Japan’s Health Policy Institute. Some local communities offer classes on children’s health emergencies to new parents, helping them understand when to call emergency services.

The “#7119” emergency consultation hotline can also assist people in determining whether an ambulance is necessary. Such services help reduce unnecessary ambulance calls.

Many areas now use alternatives like taxis for non-critical patients, and private ambulance services are being utilized to alleviate the demand on public services.

Conclusion:

The Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications reports that in 2023, the average time it took for an ambulance to arrive was about 10 minutes, with the increase in emergency calls contributing to delays. While costs like those estimated by Kobe City at 45,469 yen per dispatch demonstrate the high expense of emergency services, there is a cautious approach to formalizing fees for emergency transport. International precedents vary, from charges in New York City to healthcare-funded services in France and Germany.

This ongoing debate suggests that while some fee implementation may help reduce non-urgent ambulance use and reflect the real costs, there is also concern about potential deterrence and the equitable provision of emergency health services.

by MagazineKey4532